Ship the Book, Not the System

Here's how I escaped the Zettelkasten trap and started writing again.

A Zettelkasten Confession

156 Notes About Note-Taking

I recently encountered a very interesting and intriguing article by Steven Thompson describing his elaborate system for navigating a large Zettelkasten (Slip Box) in Obsidian. He uses Folgezettel numbering: manual sequencing showing how ideas branch. He builds MOCs, Maps of Content — hand-curated navigation documents. He employs hover-preview workflows and collapsible callouts to manage long link lists.

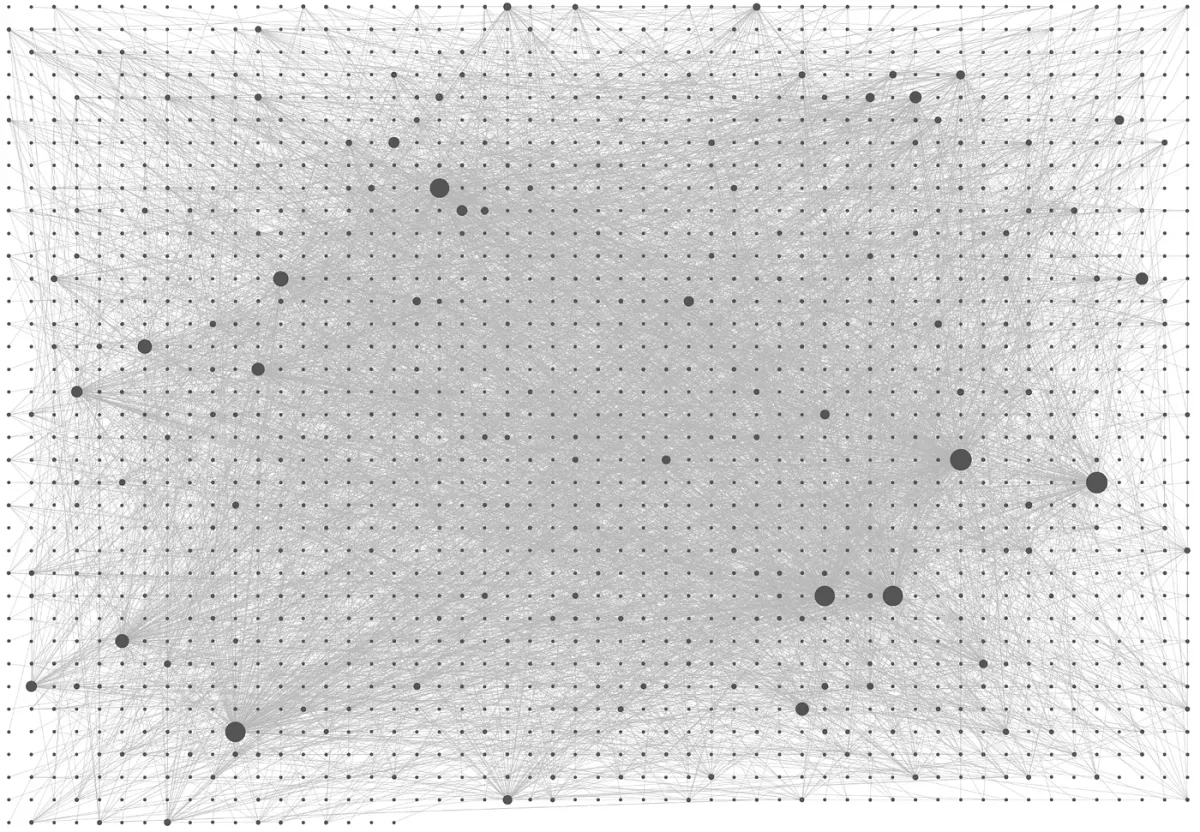

And then, almost in passing, he mentions that one of his chains contains 156 notes. The subject of this chain? Zettelkasten as Methodology.

One hundred and fifty-six notes about how to organise notes. I paused. A system describing itself. A snake eating its tail. And I recognised myself in it — because I have been there too.

Four years ago, I wrote about leaving Roam Research and Logseq. The problem then was output: the beautiful web of linked notes hit a wall when I needed to actually deliver a text. I could not compile. I could not extract. I retreated to Scrivener. But now I see that was only the surface. The deeper problem is that the linking itself becomes the subject — a system contemplating its own navel.

The Power of the Zettelkasten

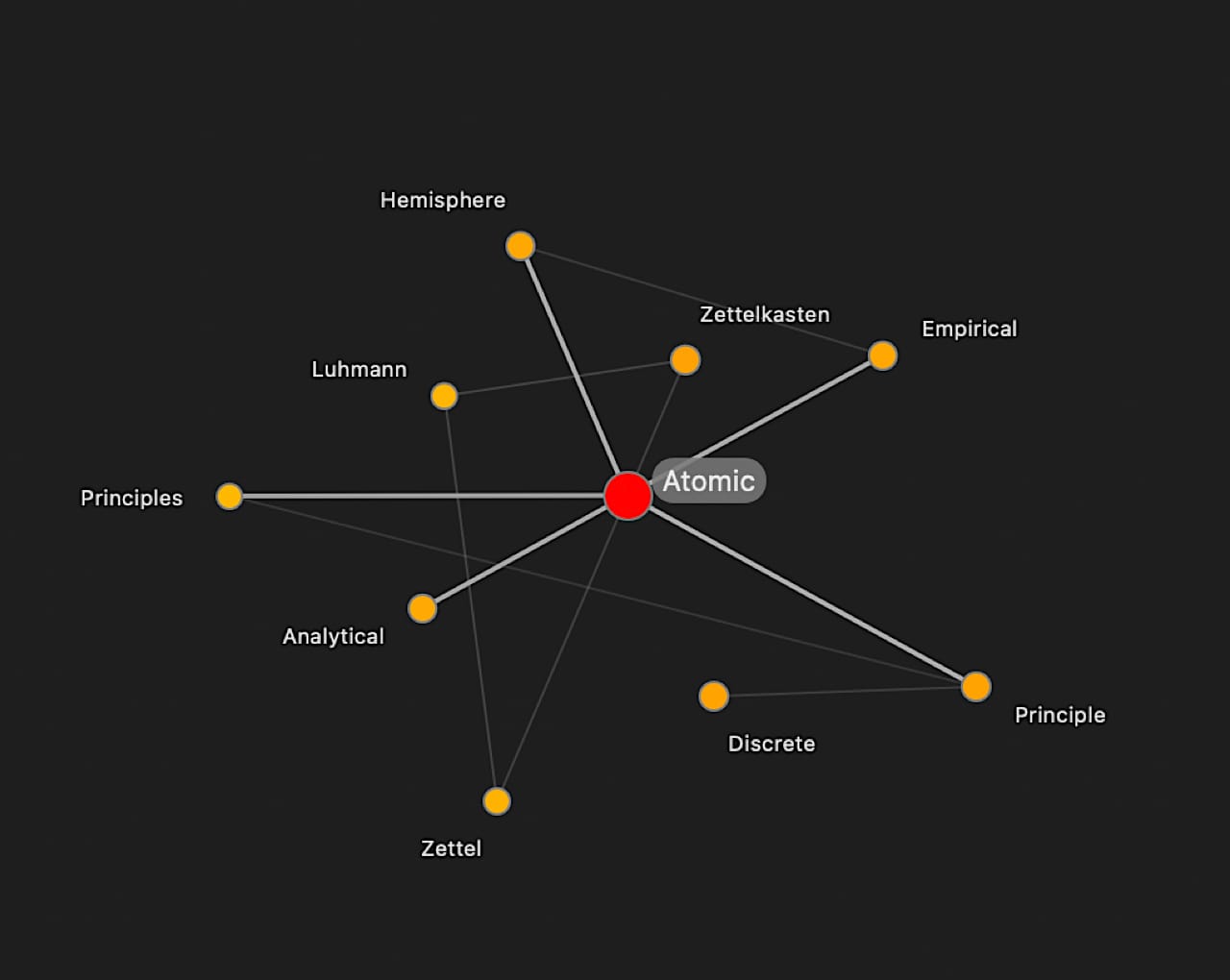

The Zettelkasten is a fantastic system. It allows me to write down thoughts, to articulate them, and to preserve them as atomic notes. The whole thing is extraordinarily powerful, because our thoughts appear to circle endlessly — but in reality, they orbit like electrons around only a relatively small number of atomic nuclei.

One might call these nuclei the core ideas or fundamental themes, and the many electrons circling around them in clouds the individual thoughts and ideas connected to them. These ideas do not, of course, arise from nothing; they are themselves associations with what we have read, heard, or lived — electrons that have broken free and entered the gravitational pull of our thematic atoms or nuclei, settling into orbit around them, in a kind of cloud best described perhaps only with the probabilities of quantum physics, not with the precise positions classical physics needs to claim.

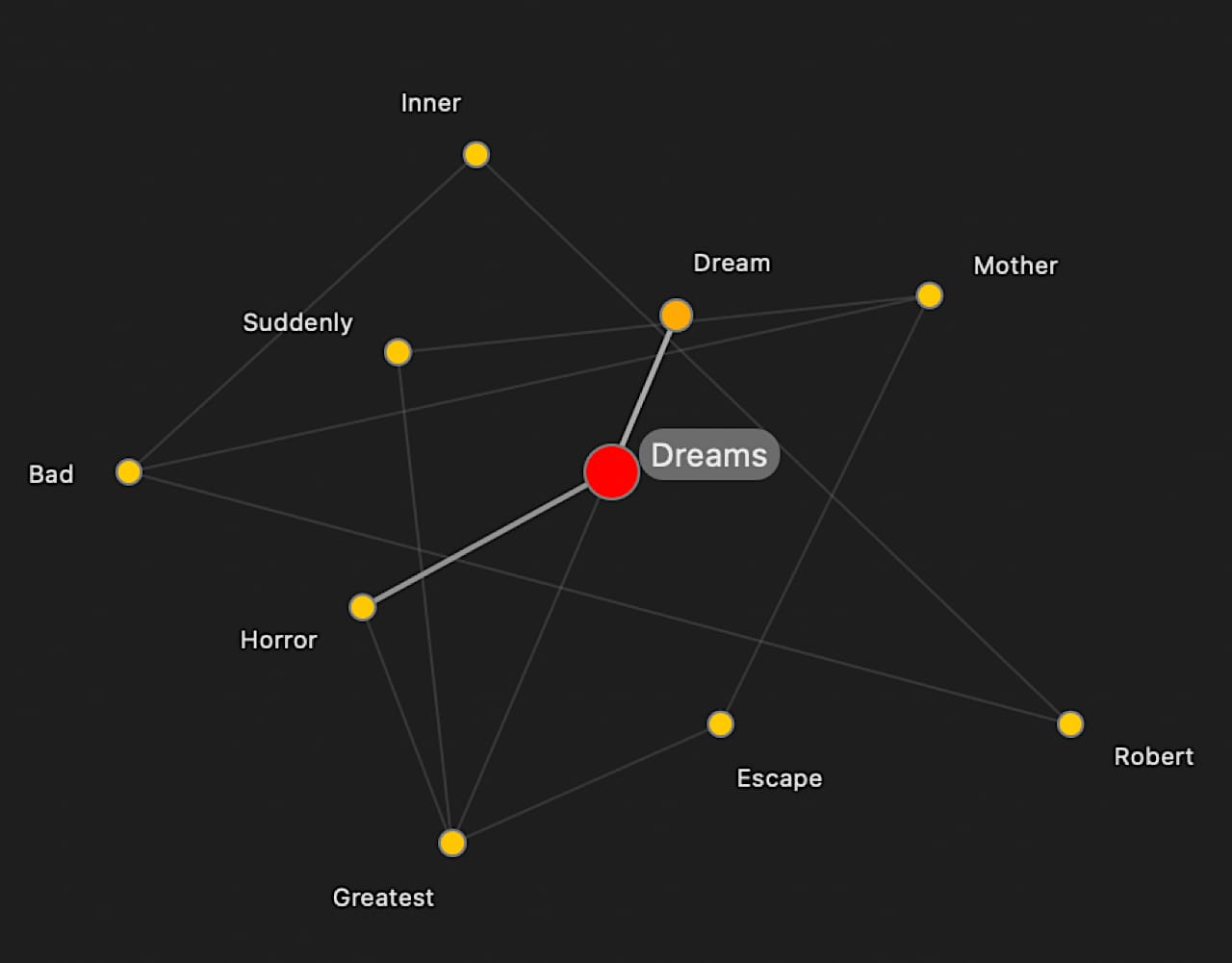

The more electrons orbit such a nucleus, the more complex the entire atom becomes. Naturally, connections between atoms will emerge. Molecules form, connections of ideas: politics snap with personally experienced emotions, art with research, science literature with fiction. Our life is complicated. Our inner life is a complex structure. It would be absurd to try to divide it into isolated themes — and yet we must somehow attempt to focus on individual atoms when we want to create something, when we want to develop articles, texts, images, theatre pieces, scientific work, or books from these themes and thoughts we have gotten hold of.

Speed and Capture

The Zettelkasten is a perfect instrument for this work. It permits quick notes — and quick notes are surely the alpha and omega. Our life is made of these quick thoughts, of sudden associations, of our thoughts on themes, investigations, inventions, discoveries. To write these down quickly — where quickly has nothing to do with velocity but with evanescence, with immediacy — to be able to capture them quickly is important, essential.

Notebooks, index cards, brief dictations into a phone, lean writing systems on phone, iPad, or computer that do not distract but only enable rapid input — for me, and I believe this is a great step for everyone concerned with knowledge management — the great step is always from the abundance of notes that accumulate to the connections between them.

From Abundance to Coherence

The power of the Zettelkasten lies precisely in this: we write a multitude of thoughts, ideas, atomic notes (I prefer calling them electrons, as in my imagination they whirl about a nucleus, the theme), and let these notes — these electrons — move through the space of the Zettelkasten. But of course we need the attractors, the atomic nuclei. We want the electrons, the individual notes, to find their nucleus and settle into their cloud around it.

So that when we have a thematic question — about quantum physics, for example — we can reach into our treasury of thoughts, into our world of notes, grasp the physics theme, and retrieve not only all the notes connected to it, but also see possible connections between the notes themselves.

I must be able to reach into my treasury of thoughts, grab a nucleus — say, the nucleus for quantum physics — and fish out all the electrons swirling in their clouds around it. These need not be notes explicitly about quantum physics. They can be connected notes: thoughts about theatre and quantum physics, or wave theory as a model for a theatrical performance, and so on. My need is about universes, not about individual points, individual thoughts, individual ideas.

Luhmann's System and Its Modern Imitations

Luhmann's Zettelkasten system, about which so much is written and spoken today, prescribes that each slip corresponds to one thought, one idea, called atomic note. An electron, in my universe. If I want to record an association or a subsequent thought, I must create a so-called Folgezettel — a follow-up note — which must, of course, be linked in one way or another to the first note. All of this Luhmann did by hand. The digital replications of this system often look astonishingly similar to Luhmann's old hand-made versions.

There are thousands of articles that describe not only the Zettelkasten technique but also propose implementations. Yet one sees again and again that most of these are not actually about the hoped-for effect of Zettelkasten work, but about a description of the system itself. Many of these articles demonstrate how the Zettelkasten is organised: the system describing itself, rather than proving its efficiency in other domains and receding into the background in service of creation.

Often the Zettelkasten, as an enormous edifice, interposes itself, demanding — in the proposals of many Zettelkasten enthusiasts — considerable attention and intellectual superstructure. It pushes itself to the foreground and fails to do the one thing it should: disappear into the background in service of creation. That is what good writing software (and hardware) does. That is what well-designed interfaces for computers, tablets, and other machines do: not to stand between human and idea, between thought and writing, between draft and elaboration — but to vanish.

The Uncomfortable Question

How much of your knowledge work is actually about the system rather than the work itself?

I ask this not to belittle anyone. Zettelkasten practitioners are intelligent, thoughtful people. The Folgezettel numbering schemes, the Map of Content (MOC) architectures, the tooling debates — these activities feel like intellectual work. They scratch the same itch. They produce the same satisfaction as a good day's writing. But they produce methodology, not manuscripts.

Thompson has 156 notes in one chain about Zettelkasten as Methodology. That is a system contemplating its own navel. And I suspect — because I have done it myself — that the hours spent building and maintaining these architectures could, or should, have been spent writing. The elaborate system becomes a form of productive procrastination. We feel busy. We feel organised. But we have not shipped the book.

My Journey: Letting the Software Work

I confess that I have travelled this entire road and have finally, finally arrived at the point where I have pushed the software — and the hardware too — out of my field of vision, and above all, I no longer let them absorb my thoughts, my thinking power. I write notes as before, but much more, as my brain and my soul and my time have much more space now. My Zettelkasten grows and flourishes. But I no longer create Maps of Content. I no longer push the electrons by hand into orbit around their nucleus, but hand that task over to a fantastic piece of software that simply takes it off my shoulders.

And it leaves my content to me. All files are plain text files on my computer. The software does nothing but look at these text files from outside, index them, and map the atomic nuclei — the clusters, the idea systems. I click on a file — and in the same instant its AI, machine learning developed 20 years before ChatGPT was even a dream, shows me all related files.

DEVONthink: A Brief History

DEVONthink was born in 2002, in the Swabian town of Bietigheim-Bissingen, Germany. Christian Grunenberg — described by the company as our mastermind since the Atari ST days — built the core technology. Eric Böhnisch-Volkmann joined in 2004 and became president of DEVONtechnologies, which incorporated that same year. The company was among the first to sell software solely online, when others still shipped bundles of CDs.

And, not to forget one crucial argument: where all (or nearly all) software companies have switched to the subscription model, I could actually buy the software in a one-time transaction. I own the program, and unless I don't want to upgrade to a next (bigger) version, I am done. This is fundamental for me, because I cannot allow a paywall between me and my thoughts. No credit card between me and my own intellectual production.

Now I have a system running locally on my computer. My content does not float around in clouds I don't control, I do not depend on management and operations of other companies I have nothing to do with, and last but not least, it is not tied to my credit card. It just runs. I just can go on writing.

From the beginning, DEVONthink was an AI application — though not in today's chatbot sense. Its artificial intelligence is a local machine learning engine that analyses the contents and locations of all documents in your database and discovers connections between them. This technology has formed the core foundation of DEVONthink since version 1.0, enabling features like the powerful search and the contextual See Also inspector.

Today, DEVONtechnologies is headquartered in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho (only they know why!). DEVONthink has evolved into multiple editions on the Mac, an iOS/iPadOS counterpart, and a sync mechanism that ties them together. On macOS, it remains the gold standard for document management, research, and personal knowledge management — distinguished by AI that works discreetly in the background as a technological foundation, not as a gimmick demanding attention, or an unseen cephalopod taking the writing part out of our hands and minds.

How DEVONthink Forms the Atoms

Here is what DEVONthink does that Luhmann could never do by hand, and that MOC-builders spend hours doing manually:

The See Also Inspector. When you select any document, DEVONthink's AI inspector shows you related documents — not because you linked them, but because the engine has analysed the semantic content of everything in your database and found genuine connections. It surfaces relationships you would never have traced yourself. This is the equivalent of the atomic nucleus forming automatically: the electrons find their orbits without your intervention.

Smart Groups. These are self-updating collections based on criteria you define once. A Smart Group called Quantum Theatre with the rule Content contains "quantum" AND Content contains "theatre" becomes a permanent home base — a Map of Content that maintains itself. You set it and forget it. The group populates automatically as new notes are created.

Auto-WikiLinks. DEVONthink can automatically recognise when the title of one document appears in the text of another and create a link. You can define aliases, so that "QM" links to your note on quantum mechanics. No manual linking required.

The Mentions Inspector. This shows you every document that references the current one — backlinks, discovered automatically.

The Classify Function. DEVONthink can suggest where a new document belongs, based on its analysis of your existing folder structure and content. The AI learns your organisation and proposes placements.

What Thompson and so many others build by hand with Folgezettel numbering, MOC stacks, and hover-preview workflows, DEVONthink provides automatically. The database itself becomes your navigation structure. You write; DEVONthink handles the cartography. Freed time for writing. Freed brainpower for dreaming.

And the best thing about DEVONthink? It may vanish today, but all my files stay with me. They are mere text files, the most stable file format ever, saved on my hard disk. Whatever happens to DEVONthink or to my computer: I just pull the backup to a new machine, no matter what operating system, no matter what text editor, and go on with my work.

The Legitimate Need: A Place to Stand

I must acknowledge a legitimate counter-argument. There is something psychologically valuable about having a place — a home base, a landing spot for a theme, for a nucleus, for an apparently real list of Zettels around a theme. When I think I need to work on quantum theatre, my brain looks for somewhere to go.

Smart Groups provide exactly this. A Smart Group is not a document you maintain; it is a living view of one or a multitude of criteria. You define its criteria once, and it becomes your permanent entry point. Every time you open it, it shows you the current state of that universe: all the electrons currently orbiting that nucleus, updated automatically.

This, for me, satisfies the need for orientation completely, and without the maintenance burden. You get the home base. You skip the gardening work. Your garden just grows beautifully.

What You Might Genuinely Lose

One thing, and only one: visible intellectual lineage. A Folgezettel chain shows your thinking sequence — how you built the argument, which idea led to which. DEVONthink's See Also shows relevance, not genealogy. It tells you what belongs together, not the path you walked to get there.

If tracing your own creative journey matters to you, a simple dated log might capture it: 7 December 2025: Connected the wave-particle duality note to the theatre of uncertainty piece because both deal with the observer's role. Ten seconds of writing. No numbering schemes. No architectural overhead. No thinking on classification.

Ship the Book

Tools should disappear into the work. The best pen is one you forget you are holding. The best software is software that does not make you think about software. It gets out of your way and becomes surface for your thoughts, ideas, dreams.

Write. Search. Trust the AI¹. Ship the book.

If you have spent more time this month organising your notes than writing new ones, perhaps it is time to ask what the system is really for.

Who is at the service of what?

¹ DEVONthink's AI is local machine learning — pattern recognition and semantic analysis running on your own computer. It is not a large language model; it does not generate text or create for you. It finds connections. You do the thinking and writing.

Questions?

What is a Zettelkasten?

A "slip box" method for organising notes, popularised by the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Each note contains one atomic idea and links to related notes. Modern apps like Obsidian, Roam Research, and Logseq digitise this system.

What are Maps of Content (MOCs)?

Hand-curated navigation documents that list and organise links to related notes. MOC builders maintain these manually to help navigate large note collections. The critique: maintaining MOCs can become the work itself.

What is DEVONthink?

A macOS document management app from DEVONtechnologies, founded in 2002 in Germany. Its built-in AI analyses your documents and automatically discovers connections — no manual linking required.

Is DEVONthink's AI like ChatGPT?

No. DEVONthink uses local machine learning — pattern recognition and semantic analysis running on your computer. It doesn't generate text or create for you. It finds connections. You do the thinking and writing.

Why use DEVONthink instead of Obsidian or Roam?

Well you use whatever you want. There are people who have written novels in Excel.

DEVONthink handles the linking automatically. You write; it maps the connections. No Folgezettel numbering, no MOC maintenance, no architectural overhead. The software disappears into the background.

What do you lose compared to a manual Zettelkasten?

Visible intellectual lineage. A Folgezettel chain shows your thinking sequence — which idea led to which. DEVONthink shows relevance, not genealogy. If that matters, keep a simple dated log instead.

References:

Steven Thompson's article on MOC stacks in Obsidian: Obsidian Page Preview and MOC Stack

Opus 4.5 has been used for research and help in translation.